A split verdict that reshapes the case

The Sean Combs verdict landed with a jolt: a New York jury cleared the music mogul of the most explosive charges—racketeering conspiracy and sex trafficking—yet found him guilty on two counts of transportation to engage in prostitution. Each count carries a maximum sentence of 10 years, leaving the 55-year-old facing a potentially lengthy prison term even as prosecutors’ biggest claims fell short.

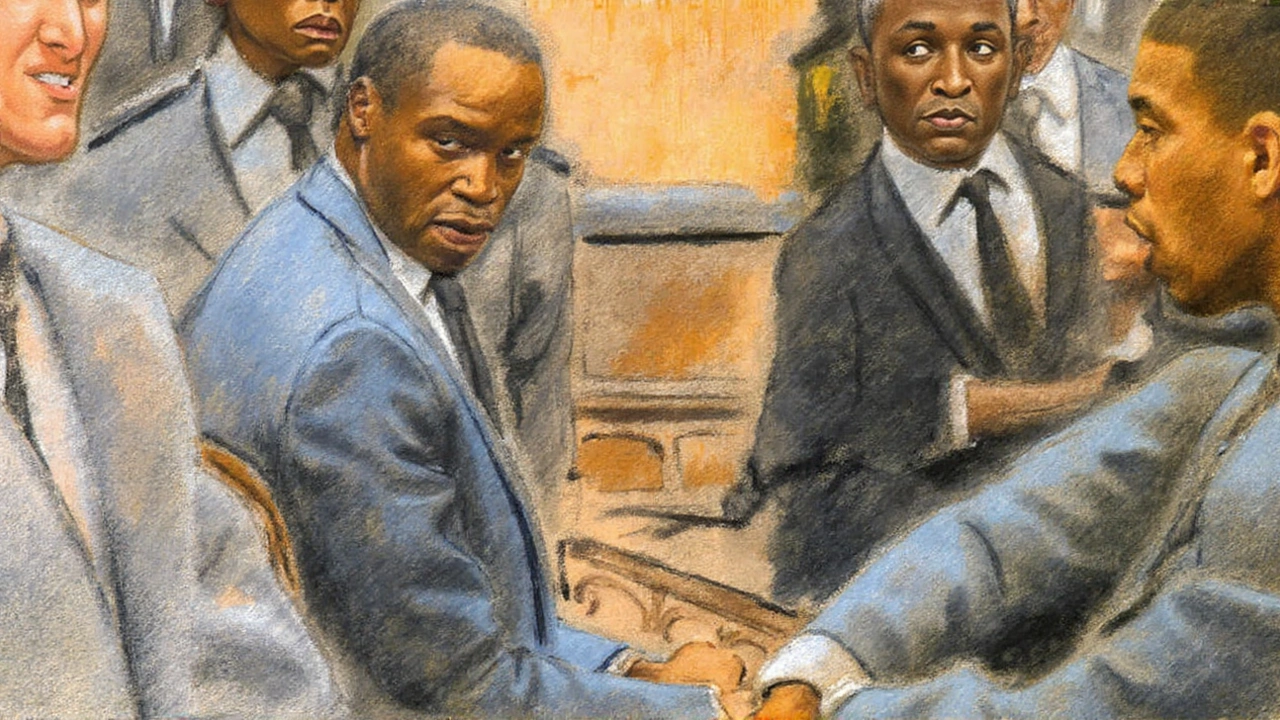

As the clerk read the decision, Combs turned, kneeled, pressed his hands to his chair, and prayed. His family erupted in cheers. The celebration stopped at the courtroom doors. Prosecutors urged Judge Arun Subramanian to keep him in custody until sentencing, and the judge did—continuing a bail denial that has kept Combs at the Metropolitan Detention Center in Brooklyn since earlier in the case.

The split decision ends a month-and-a-half trial that pulled back the curtain on the private life of one of hip-hop’s most powerful figures. Prosecutors called more than 30 witnesses to argue that Combs ran a coercive operation that forced women into sex acts. Jurors didn’t buy the racketeering or sex trafficking conspiracy. They did, however, conclude that Combs was criminally responsible for transporting individuals for prostitution.

That transportation charge is a long-standing federal offense often associated with cases involving crossing state lines for illicit sex acts. It sits in a different legal lane from sex trafficking and racketeering, which require proof of an enterprise or coercion at a high bar. The jury’s line-drawing suggests they were persuaded by some alleged conduct but unconvinced that the government proved the broader criminal scheme beyond a reasonable doubt.

Combs didn’t testify. His defense leaned on cross-examinations and a simple pitch: prosecutors had stretched consensual adult behavior—threesomes, parties, drugs—into criminal racketeering. "He did not do the things he's charged with," defense attorney Marc Agnifilo told jurors, calling the case an exaggeration dressed up as conspiracy.

Among the most closely watched moments in the trial was the testimony of singer and model Cassandra “Cassie” Ventura, Combs’ former partner. Ventura had filed a civil lawsuit in 2023 that settled a day later for $20 million. Her attorney, Douglas H. Wigdor, said her decision to come forward helped kick-start the criminal probe. After the verdict, he noted that while jurors rejected sex trafficking, they did find the transportation-for-prostitution counts proven.

The courtroom drama also played against the backdrop of a video from 2016 that prosecutors repeatedly cited: surveillance footage from a hotel showing Combs kicking and dragging Ventura. Judge Subramanian pointed to that video when denying bail on August 4, calling Combs both a flight risk and a danger to the community. The judge’s order has kept Combs in federal detention as his legal team prepares its next moves.

What the ruling means now: detention, motions, and sentencing

Combs’ lawyers immediately pushed to send him home to Miami, arguing this is his first conviction and that he has every incentive to follow court orders. The government pushed back, and for now, he stays at MDC Brooklyn. The focus turns to two key dates: a post-trial motions hearing on September 25 in Manhattan and sentencing set for October 3, 2025.

At the September hearing, expect the defense to ask the judge to toss the convictions or grant a new trial. Those requests—commonly known as Rule 29 (judgment of acquittal) and Rule 33 (new trial) motions—are a long shot. Judges rarely overturn jury verdicts unless the evidence was clearly insufficient or serious trial errors tainted the outcome. Prosecutors already previewed their opposition, saying there was more than enough in the record to uphold the convictions.

If the verdict stands, sentencing will hinge on federal guidelines that weigh several factors: the offense conduct, any aggravating details, and Combs’ criminal history. Each count carries up to 10 years. Judges can run terms at the same time or back-to-back, and they can add supervised release, fines, and special conditions. Prosecutors say they’ll seek a lengthy sentence. Because Combs went to trial, he won’t get the common “acceptance of responsibility” reduction that sometimes trims guideline ranges after a guilty plea.

One reason the custody fight is so fierce: pre-sentencing detention telegraphs risk. Judges don’t lock people up before sentencing lightly. Here, Judge Subramanian pointed directly to the 2016 video of violence toward Ventura as evidence of danger to the community. He also cited concerns about flight, a factor that can loom large when a defendant has significant resources and international ties.

Still, the acquittals matter—legally and publicly. Racketeering conspiracy, often used in cases alleging a structured criminal enterprise, and sex trafficking both require proof of specific elements: patterns, control, or coercion at a high standard. Jurors didn’t see those charges made out beyond a reasonable doubt. The convictions, meanwhile, reflect a narrower slice of conduct—transportation for prostitution—that the jury found supported by evidence.

For Combs, the immediate reality is stark: awaiting sentencing in federal custody. For his lawyers, the mission is clear: attack the convictions on legal grounds now, and, if those fail, press for the lowest possible sentence. For prosecutors, the job is to defend the verdict and argue that the conduct warrants serious time.

Key dates ahead:

- Motion hearing: September 25 (Manhattan federal court). Defense will seek acquittal or a new trial; prosecutors oppose.

- Sentencing: October 3, 2025. Prosecutors have said they will ask for a lengthy prison term.

The case also shows how civil claims can trigger criminal consequences. Ventura’s 2023 lawsuit—filed and settled within 24 hours—became the starting gun for a broader federal inquiry that eventually produced the split verdict. That sequence, now common in high-profile cases, underscores how parallel civil and criminal paths can intersect, even if they land in different places.

However the sentencing shakes out, the music industry is staring at a recalibration. The government didn’t persuade jurors that Combs ran a trafficking or racketeering enterprise. It did convince them he broke federal law by arranging transportation tied to prostitution. That gray zone—between private, adult behavior and crimes prosecuted in federal court—is where this case now sits, heading into a crucial fall calendar that will decide Combs’ future.

5 Comments

It is imperative that we uphold a clear moral standard when public figures are accused of exploiting vulnerable individuals, and the verdict underscores the importance of accountability even when some charges are dismissed.

I can’t imagine how painful this whole process must have been for everyone involved, especially the survivors who had to relive trauma during the trial 😊. The mixed emotions are understandable, and I hope the legal system continues to protect victims while ensuring a fair process for the accused.

Looking at the split verdict reminds us that the law tries to balance nuance, not just black and white, and that’s a lesson we can apply to many contentious issues.

The jury’s decision illustrates how a courtroom can become a crucible for societal values, where every piece of evidence is weighed against the backdrop of public perception, and where jurors must parse the fine line between consensual adult behavior and criminal conduct, which is no easy task, especially when high‑profile figures are involved, and the media narrative often skews the facts, creating pressure that can influence deliberations, and yet the jurors adhered to the standard of proof beyond a reasonable doubt, acquitting on the most severe charges, which underscores the strength of the defense’s argument that the prosecution overreached, while still finding enough proof for the transportation‑for‑prostitution counts, showing that the evidence there was more concrete, perhaps including communications, travel records, or testimonies that linked Combs directly to the prohibited activity, and that distinction matters because it reflects the jury’s willingness to differentiate between degrees of culpability, a crucial point for future cases involving similar allegations, and it also sends a message to prosecutors that they must present a cohesive narrative supported by solid proof, not just conjecture or sensationalism, the outcome may also influence how civil settlements like Cassie Ventura’s are viewed, as they can act as catalysts for criminal investigations, highlighting the interplay between civil and criminal law, and finally, this case will likely be studied in law schools as an example of how federal statutes operate differently depending on the specific elements required to prove each charge, reminding us that the legal system is layered, complex, and ultimately designed to protect both victims and the rights of the accused.

Justice must be balanced.